SEASONS OF FIRES

In the History of the Egyptian Cinema

Seasons of Fires

Anonymous

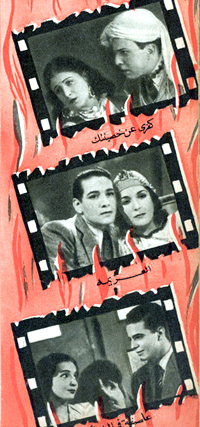

As fate would have it, a fire broke out in Studio Misr in the year of the Egyptian cinema’s silver jubilee. Its victims were a number of old films that had been put in a special store room in the basement of the studio. From there, the fire spread to the Montage Section next to it and consumed some new films which were to be released that season: Nahed, directed by Mohamed Karim for Raqia Ibrahim; Heart to Heart (el Qalb lel qalb) directed by Barakat for Assia; Faith (el Imân) directed by Badrakhan; Night Train (Qitâr el layl)directed by Ezzedine Zulficar ; and The Good Citizen (el Mouwatin el salih) directed by Gamal Madkour for the Ministry of Health. Other victims of the fire were equipment for the montage and screening of films, all of the latest technology developed by manufacturers of cinema equipment. That was the worst event in the year of the Egyptian cinema’s silver jubilee, but it was not the first of its kind in the history of our cinema. There had been other fires before, some causing heavy losses, and others that were minor.

As fate would have it, a fire broke out in Studio Misr in the year of the Egyptian cinema’s silver jubilee. Its victims were a number of old films that had been put in a special store room in the basement of the studio. From there, the fire spread to the Montage Section next to it and consumed some new films which were to be released that season: Nahed, directed by Mohamed Karim for Raqia Ibrahim; Heart to Heart (el Qalb lel qalb) directed by Barakat for Assia; Faith (el Imân) directed by Badrakhan; Night Train (Qitâr el layl) directed by Ezzedine Zoulficar; and The Good Citizen (el Mouwatin el salih) directed by Gamal Madkour for the Ministry of Health. Other victims of the fire were equipment for the montage and screening of films, all of the latest technology developed by manufacturers of cinema equipment. That was the worst event in the year of the Egyptian cinema’s silver jubilee, but it was not the first of its kind in the history of our cinema. There had been other fires before, some causing heavy losses, and others that were minor.

When he directed Child of the Desert (Ibn el Sahraa) in 1942, Ibrahim Lama did what the late Kamal Selim had done. A fire broke out in Studio Lama, which contained all the old films as well as the new ones, including the above mentioned film. Without thinking, Ibrahim Lama rushed into the store house to combat the flames and save what he could of the film boxes. These included a great number of rare “raw” films dating to the period of World War II. His face and arms were so severely burned that he had to be taken to hospital for treatment. The negative of Child of the Desert (Ibn el Sahraa) perished in the flames, so he had to shoot it again after he left hospital.

As with Studio Misr, there was another fire in Studio Lama two years ago. It was around noon when the grand plateau caught fire. Samir Abdallah and the photographer Rashad Salama were fixing the sound of the film A Storm in Spring (‘Âsifah fi-l-rabî') when the room suddenly burst into flames. Samir and the photographer managed to escape before the fire surrounded them. Ibrahim was then in the lab of Studio Nassibian in Faggala. As soon as he was notified by phone he hurried to the studio, only to find that the tongues of flame had eaten the grand plateau and all the equipment and electric lamps it contained. They had just been bought by the deceased Ibrahim Lama from the States when he had traveled there, and were being used for the first time. As the fire had consumed the boxes of the film A Storm in Spring (‘Âsifah fi-l-rabî')in the sound room, the film was re-shot.

There was also a fire in Abdel Wahab’s Film Company, when it was situated in El Saha Street, Rushdi Pasha, next to Omar Effendi Stores. One night, people saw smoke coming out of the windows of the second floor flat where the administration of the company was. The fire department was notified, as well as Mr. Abdel Wahab and Mr. Karim, who both hurried there to save as many film boxes as possible. The fire was quickly contained and prevented from spreading to the other parts of the building which were inhabited by residents.

We finally go back to 1932, when Mrs. Aziza Amir had finished producing her film Repent your Sin (Kaferi ‘an Khatî’tek). One night, she was in her apartment in Zamalek, preparing the boxes she would send to a cinema that would run the film on trial after midnight, before it was to premiere properly. Suddenly Aziza heard a small “pop” that she did not pay attention to. Then, after the pop, there was a whistle and a hissing like that of a snake. Aziza felt some heat beneath her feet. She raised her eyes, only to see tongues of flame spreading quickly and surrounding her from all sides. She forgot herself and tried to save what she could of the film, while the fire spread throughout the room and to the furniture and the film boxes. In a split second the room had turned into an inferno. Aziza tried to escape but couldn’t because of the density of the smoke clouds. Outside the room, her mother screamed. The neighbours and passers by saw the flames spread outside the house. Voices rose, asking for help. Zeinab Sedki, who lived in the same building, screamed like a madwoman, and, calling out Aziza’s name, rushed into the midst of the flames to save her. Aziza had fainted. She carried her in her arms outside the house. The firemen had arrived. They surrounded the fire and worked their pumps till they put it out. But the box of the positive of the film Repent your Sin (Kaffiri ‘an Khati’atek) had burned in the fire. Luckily, the box containing the negative had not been in the room, or Aziza’s loss would have been tremendous.

El Kawakeb. Issue No. 33. October 1951.