| front |1 |2 |3 |4 |5 |6 |7 |8 |9 |10 |11 |12 |13 |14 |15 |16 |17 |18 |19 |20 |21 |22 |23 |24 |25 |26 |27 |28 |29 |30 |31 |32 |33 |34 |35 |36 |37 |38 |39 |40 |41 |42 |43 |44 |45 |46 |47 |48 |49 |50 |51| 52 |53 |54 |review |

|

By the beginning of World War II, there was concern among scientists in the Allied nations that Nazi Germany might have its own project to develop fission-based weapons. Organized research first began in Britain as part of the "Tube Alloys" project, and in the United States a small amount of funding was given for research into uranium weapons starting in 1939 with the Uranium Committee under Lyman James Briggs. At the urging of British scientists, though, who had made crucial calculations indicating that a fission weapon could be completed within only a few years, by 1941 the project had been wrested into better bureaucratic hands, and in 1942 came under the auspices of a Military Policy Committee led by General Leslie Groves as the Manhattan Project. Scientifically led by the American physicist Robert Oppenheimer, the project brought together the top scientific minds of the day (many exiles from Europe) with the production power of American industry for the goal of producing fission-based explosive devices before Germany could. Britain and the U.S. agreed to pool their resources and information for the project, but the other Allied power—the Soviet Union under Joseph Stalin—was not informed. Until the atomic bomb could be tested, doubt would remain about its effectiveness. The world had never seen a nuclear explosion before, and estimates varied widely on how much energy would be released. Some scientists at Los Alamos continued privately to have doubts that it would work at all. There was only enough weapons-grade uranium available for one bomb, and confidence in the gun-type design was high, so on July 14, 1945, most of the uranium bomb ("Little Boy") began its trip westward to the Pacific without its design having ever been fully tested. A test of the plutonium bomb seemed vital, however, both to confirm its novel implosion design and to gather data on nuclear explosions in general. Several plutonium bombs were now "in the pipeline" and would be available over the next few weeks and months. It was therefore decided to test one of these.

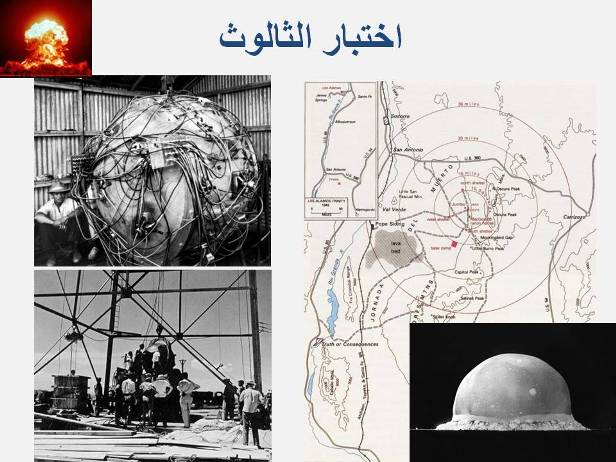

Robert Oppenheimer chose to name this the "Trinity" test, a name inspired by the poems of John Donne. The site chosen was a remote corner on the Alamagordo Bombing Range known as the "Jornada del Muerto," or "Journey of Death," 210 miles south of Los Alamos. The elaborate instrumentation surrounding the site was tested with an explosion of a large amount of conventional explosives on May 7. Preparations continued throughout May and June and were complete by the beginning of July. Three observation bunkers located 10,000 yards north, west, and south (right) of the firing tower at ground zero would attempt to measure key aspects of the reaction. Specifically, scientists would try to determine the symmetry of the implosion and the amount of energy released. Additional measurements would be taken to determine damage estimates, and equipment would record the behavior of the fireball. The biggest concern was control of the radioactivity the test device would release. Not entirely content to trust favorable meteorological conditions to carry the radioactivity into the upper atmosphere, the Army stood ready to evacuate the people in surrounding areas.

On July 12, the plutonium core was taken to the test area in an army sedan (right). The non-nuclear components left for the test site at 12:01 a.m., Friday the 13th. During the day on the 13th, final assembly of the "Gadget" (as it was nicknamed) took place in the McDonald ranch house. By 5:00 p.m. on the 15th, the device had been assembled and hoisted atop the 100-foot firing tower.

During the final seconds, most observers laid down on the ground with their feet facing the Trinity site and simply waited. At precisely 5:30 a.m. on Monday, July 16, 1945, the nuclear age began. While Manhattan Project staff members watched anxiously, the device exploded over the New Mexico desert, vaporizing the tower and turning the asphalt around the base of the tower to green sand. Seconds after the explosion came a huge blast wave and heat searing out across the desert. No one could see the radiation generated by the explosion, but they all knew it was there. The steel container "Jumbo," weighing over 200 tons and transported to the desert only to be eliminated from the test, was knocked ajar even though it stood half a mile from ground zero. As the orange and yellow fireball stretched up and spread, a second column, narrower than the first, rose and flattened into a mushroom shape, thus providing the atomic age with a visual image that has become imprinted on the human consciousness as a symbol of power and awesome destruction.

About 40 seconds after the explosion, Fermi stood, sprinkled his pre-prepared slips of paper into the atomic wind, and estimated from their deflection that the test had released energy equivalent to 10,000 tons of TNT. The actual result as it was finally calculated -- 21,000 tons (21 kilotons) -- was more than twice what Fermi had estimated with this experiment and four times as much as had been predicted by most at Los Alamos. The next day, Stimson, informed that the uranium bomb would be ready in early August, discussed Groves's report at great length with Churchill. The British prime minister was elated and said that he now understood why Truman had been so forceful with Stalin the previous day, especially in his opposition to Russian designs on Eastern Europe and Germany. Churchill then told Truman that the bomb could lead to Japanese surrender without an invasion and eliminate the necessity for Russian military help. He recommended that the President continue to take a hardline with Stalin. Truman and his advisors shared Churchill’s views. The success of the Trinity test stiffened Truman's resolve, and he refused to accede to Stalin's new demands for concessions in Turkey and the Mediterranean. On July 24, Stimson met again with Truman. He told the President that Marshall no longer saw any need for Soviet help, and he briefed the President on the latest atomic situation. The uranium bomb might be ready as early as August 1 and was a certainty by August 10. The plutonium weapon would be available by August 6. Stimson continued to favor making some sort of commitment to the Japanese emperor, though the draft already shown to the Chinese was silent on this issue. Truman now had to decide how he would deliver the news of the atomic bomb to Stalin. Unbeknownst to Truman, the Soviet leader already knew.

The success of the Trinity test meant that both types of bombs -- the uranium design, untested but thought to be reliable, and the plutonium design, which had just been tested successfully -- were now available for use in the war against Japan. Little Boy, the uranium bomb, was dropped first at Hiroshima on August 6, while the plutonium weapon, Fat Man, followed three days later at Nagasaki on August 9. Within days, Japan offered to surrender. |